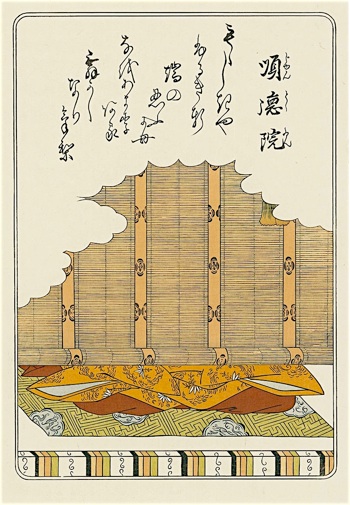

順徳院御製

百敷や

古き軒端の

しのぶにも

なほあまりある

昔なりけり

じゅんとくいん

ももしきや

ふるきのきばの

しのぶにも

なおあまりある

むかしなりけり

Emperor Juntoku

In this hundred-stone palace

The ancient eaves

Are overgrown with ferns,

That is what is left alas

Of times gone by.

Katsukawa Shunsho/David Bull

Juntoku-In (1197 - 1242) reigned as an emperor from 1210 to 1221. His personal name was Morinari-shinno. Posthumously he was also known as Sado-no-In (from the island where he spent his last years). He was the third son of Emperor Gotoba (poem 99) and was adopted by Shokushi (poem 89). In 1221, he was forced to abdicate because of his participation in Gotoba's unsuccessful attempt in the Jokyu war to remove the Kamakura bakufu and reinstate imperial power, and was subsequently exiled to the island Sado.

Juntoku was tutored in poetry by Teika (poem 97). There are 159 of his poems in imperial collections. A collection of his personal poetry is extant. He also wrote the Kimpisho (about royalty and court), and a voluminous poetic work, the Yakumo Misho, a poetry encyclopedia.

This poem was written in 1216. Yoshua Mostow notes that “the collection ends, as it began, with a parent-child set of poems (Tenji - Jito and Gotoba - Juntoku).

Juntoku is deploring the decline of righteous government and the fortunes of the imperial house. As such, the poem is seen as the pendant to the first poem in the anthology, attributed to Emperor Tenji (poem 1), also frequently interpreted as a lament over the decline of imperial authority.”

However, the first poem in this anthology is much more pastoral, much softer. I don’t see poem 1 as being concerned so much about the decline of imperial authority, rather it’s the typical Japanese concern with the ephemerality of life in general.

Teika’s anthology is a thoughtfully compiled collection of poems. This last poem begins with the word momo, ‘hundred’ and momoshiki is the imperial palace ‘paved with one hundred stones’. Shinobu is a fern, and also means ‘to long for, be nostalgic about, admire, praise for beauty’; it is sometimes translated as ‘memory fern’ or ‘longing fern’.

This last poem can be considered the swansong of the Heian era, the end of a historic period of aristocratic elegance and refinement, a period in which the aristocracy conversed in verse. There is a definite shift in concern from the first poems to the last ones. Where the first ones can be called pastoral, the shift goes to a sentiment of decay. But all through the anthology there is a concern with the transience of worldly life, so typical of the Buddhist and Japanese spirit. The experience of nature and life seemlessly combines with personal feelings into a wording that blends both into an indissoluble unity.

It is a pity there is no Hokusai woodcut for this poem. So the curtain falls with a woodcut by David Bull from a design by Katsukawa Shunsho (1726-1792).

Shinobu, Davallia mariesii