大納言公任

滝の音は

絶えて久しく

なりぬれど

名こそ流れて

なほ聞こえけれ

だいなごんきんとう

たきのおとは

たえてひさしく

なりぬれど

なこそながれて

なおきこえけれ

Fujiwara no Kinto

The sound of the waterfall

Has ceased long ago

And its flow dried up,

Yet in name it ever flows

And in fame will still be heard.

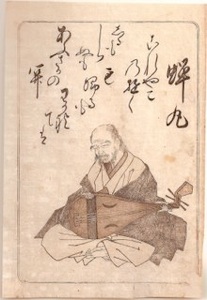

Hokusai

Fujiwara no Kinto (966-1041), also known as Shijo Dainagon, was a poet and nobleman. His father was regent Fujiwara no Yoritada and his son was Fujiwara no Sadayori (poem 64). He was a grandson of Tadahira (poem 26). An exemplary calligrapher and poet, he is given mention in works by Murasaki Shikibu, Sei Shonagon and several others). He initiated the grouping of poets into the Thirty-Six Immortal Poets. He wrote the Waka Kuhon and the Shinsen Zuino, treatises about poetry. In 1024 he became a Buddhist monk.

Kinto by Kikuchi Yosai

May the fame of this waterfall, na koso no taki, go on for ages. It is situated on the premises of the Daikakuji, the Daikaku Temple. In 794 Emperor Kammu relocated the capital to Kyoto, which was the beginning of the Heian period. Twenty years later Emperor Saga succeeded to the throne. He loved this remote land of Sagano and built here a new palace, the Saga-in. This is the origin of the Saga-rikyu or imperial villa, which later became the Daikakuji. (English website) The waterfall was constructed by order of emperor Saga, but had already dried up at the time Kinto lived there as a monk.

On the left of Hokusai’s drawing we see a tree and further to the right there is another shape that resembles very much this first tree, but could as well be a wild waterfall or rocks. Maybe this was his way of saying the waterfall lives on in the trees there. The long dark stripes behind the rocks or trees could represent the waterfall, but the unfinished state of this woodcut does not make this clear. He may as well have shown the site without any water. People are picknicking, playing music, probably talking or singing about the waterfall, and certainly enjoying themselves. The women would not be playing the shamisen if this were a wild, thundering waterfall.

The earlier versions of this poem have taki no ito (the strings of the waterfall) instead of taki no oto (the sound of the waterfall) in the first line. There is a play of words around ‘sound’ and ‘flow’, referring both to the waterfall and to its renown.