Tijdens de discussiebijeenkomst over Urban Parks, stadsparken, in Pakhuis de Zwijger een paar dagen geleden, zei een van de aanwezigen dat onze parken naar de filistijnen gaan. Die verzuchting lijkt wel universeel. In 1872 schreef Frederick Law Olmsted, de ontwerper van Central Park in New York, een stuk dat ingekort in Lapham’s Quarterly verscheen als Defending his Park Against the Philistines (uit: A Review of Recent Changes, and Changes Which Have Been Projected, in the Plans of the Central Park, gepubliceerd in American Earth, Library of America).

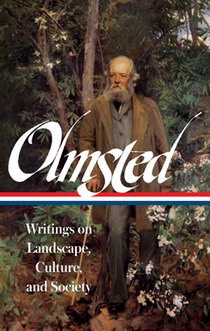

The Library of America heeft ook een uitgave van Olmsteds geschreven werk over landschap, cultuur en maatschappij, Olmsted - Writings on Landscape, Culture and Society. Onze bestuurders gaan maar al te graag op studiebezoek naar New York, maar zien niet hoe het Central Park is bedacht en ontworpen, namelijk als een natuurlijk gebied voor de stadsbewoners, waar ze de stad kunnen ontvluchten, waar ze geen hoge gebouwen meer zien, waar ze diverse landschapjes aantreffen die telkens een ander uitzicht bieden. Parken moeten de drukte, het lawaai van de stad doen vergeten, en leveren pas een echte heilzame groenbeleving als de bebouwing daar uit het beeld verdwijnt. Toch zien onze ambtenaren de parken eerder als een mooi uitzicht vanuit dure vastgoedprojecten. Het groen langs de Gaasperplas moet uitgedund worden zodat de Gaasperplas vanaf de weg en de wijken te zien is. Daarmee verdwijnt de gezonde groenbeleving volledig. Olmsted vond ook dat de parken van iedereen zijn, niet enkel van de yuppen die daar hun eigen faciliteiten en voorzieningen willen, en tegenwoordig ook festivals. De parken zijn van en voor het volk, voor recreatie, niet voor exploitatie. Parken gedurende de mooiste tijd van het jaar afsluiten voor evenementen voor een verwende en hedonistische jeugd is een gotspe. Men brengt de nadelen, het rumoer, de reuring van de stad naar de parken en vernietigt ze op die manier.

Olmsted: “As the city grows larger, projects for the public benefit multiply, land becomes more valuable, and the Park more and more really central …

… for what worthy purpose could the city be required to take out and keep excluded from the field of ordinary urban improvements a body of land in what was looked forward to as its very center, so large as that assigned for the park? For what such object of great prospective importance would a smaller body of land not have been adequate?

To these questions a sufficient answer can, we believe, be found in the expectation that the whole of the island of New York would, but for such a reservation, before many years be occupied by buildings and paved streets; that millions upon millions of men were to live their lives upon this island, millions more to go out from it or its immediate densely populated suburbs only occasionally and at long intervals, and that all its inhabitants would assuredly suffer, in greater or less degree, according to their occupations and the degree of their confinement to it, from influences engendered by these conditions. The narrow reservations previously made offered no relief from them because they would soon be dominated by surrounding buildings, and because the noise, bustle, confinement, and noxious qualities of the air of the streets would extend over them without important mitigation.

Provisions for the improvement of the ground, however, pointed to something more than mere exemption from urban conditions: namely, to the formation of an opposite class of conditions, conditions remedial of the influences of urban conditions. Two classes of improvements were to be planned for this purpose: one directed to secure pure and wholesome air, to act through the lungs; the other to secure an antithesis of objects of vision to those of the streets and houses which should act remedially, by impressions on the mind and suggestions to the imagination.

The question of localizing or adjusting these two classes of landscape elements to the various elements of the natural topography of the Park next occurs, the study of which must begin with the consideration that the Park is to be surrounded by an artificial wall twice as high as the Great Wall of China composed of urban buildings. Wherever this should appear across a meadow view, the imagination would be checked abruptly at short range. Natural objects were thus required to be interposed, which, while excluding the buildings as much as possible from view, would leave an uncertainty as to the occupation of the space beyond, and establish a horizon line, composed as much as possible, of verdure. No one looking into a closely grown wood can be certain that at a short distance back there are not glades or streams, or that a more open disposition of trees does not prevail.

A range of high woods, then, or of trees so disposed as to produce an effect when seen from a short distance looking outwardly from the central parts of the park of a natural wood-side, must be regarded as more nearly indispensable to the purpose in view—that of relieving the visitor from the city—than any other available feature.”

Trees in Streets and in Parks: "There is an association between scenes and objects such as we are apt to call simple and natural, and such as touch us so quietly that we are hardly conscious of them.

Many of the latter class, while they have been the solace and inspiration of the most intelligent and cultivated men the world has known, have been enjoyed by cottagers in peasant villages, living all their lives in a meagre and stinted way. It is folly, therefore, to say of the art that would provide these forms of recreation, either that it is too high for some or too low for others.

But this is to be said and said sadly: As a result of the massing of population in cities; of the centering of communication in cities; of the increasing resort to cities for recreation; of the tendency of fashions to rise in and go out from the wealthy class in cities; of the prominence given by the press to the latest matters of interest to the rich and the fashion-setting classes, and of the natural assumption that people of great wealth get that for themselves that is most enjoyable—as a result of all this—the population of our country is being rapidly educated to look for the gratification of taste, to find beauty, and to respect art, in forms not of the simple and natural class; in forms not to be used by the mass domestically, but only as a holiday and costly luxury, and with deference to men standing as a class apart from the mass.

All this tends to our impoverishment through the obscuration, supercession and dissipation of tastes which, under our older national habits, and especially under our older village habits, were productive of a great deal of happiness, and a most important source of national wealth.

And I submit that, both in the planting of village streets and in the planting of town parks, this tendency is rather to be resisted by sanitarians than to be enthusiastically pursued."